|

Case Report

Threatened corneal graft rejection and ocular inflammation after SARS-CoV-2 infection and influenza vaccine

1 Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institution, Waltham, MA, United States

2 The Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation, Waltham, MA, United States

3 Harvard Medical School, Department of Ophthalmology, Boston, MA, United States

Address correspondence to:

Charles Stephen Foster

MD, FACR, FACS, Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institution, 1440 Main St., Ste. 201, Waltham, MA,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100037Z17AD2023

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Dolinko AH, Maleki A, Foster CS. Threatened corneal graft rejection and ocular inflammation after SARS-CoV-2 infection and influenza vaccine. J Case Rep Images Opthalmol 2023;6(1):9–12.ABSTRACT

Introduction: To report the case of an individual who developed autoinflammation after contracting Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and receiving an influenza vaccination.

Case Report: A 61-year-old woman presented to us after two episodes of recurrent, acute, partial-thickness corneal graft rejection; the first of these began five months after Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and shortly after influenza vaccination. Best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes, and anterior chambers showed no evidence of inflammation. Fluorescein angiogram revealed disc staining in both eyes, and B-scan showed chorioretinal thickening in the left eye. She was diagnosed with posterior scleritis of the left eye and started on naproxen 500 mg twice daily with acyclovir 400 mg daily. This treatment regimen allowed her pain to resolve. Serology showed evidence of systemic inflammation with elevated antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and ocular inflammation was controlled with systemic immunomodulatory therapy.

Conclusion: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 infection may induce a long-term, systemic autoinflammatory state that may be provoked by further immune challenges, such as influenza vaccination, resulting in ocular inflammation.

Keywords: Cornea graft rejection, COVID-19, Influenza vaccination, Posterior scleritis, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, is a devastating disease that has affected over 700 million individuals and caused over 6 million deaths worldwide [1]. In more severe cases, COVID-19 can induce profound, systemic inflammation with significant elevations in inflammatory markers [2]. This pro-inflammatory state may result in a chronic, systemic autoimmune condition, such as the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) [3]. However, many chronic illnesses persisting or appearing post-COVID-19 are less well-characterized. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined “post-COVID condition” as an illness arising after COVID-19 infection and persisting for at least two months that cannot be explained by another diagnosis; such symptoms may fluctuate or relapse [4].

In our case report, we will discuss a patient with a post-COVID condition of systemic inflammation inducing symptoms of corneal graft rejection. Corneal graft rejection is rare; however, viruses including COVID-19 and other stressors stimulating an immune response can induce graft rejection [5]. Cases of graft rejection following influenza immunizations have also been reported [6]. In the case herein, we discuss a patient who had threatened graft rejections after COVID-19 infection and subsequent influenza vaccination.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman presented to us with left eye (OS) pain and light sensitivity. She had been diagnosed with endothelial cell decompensation of the left eye, and she underwent Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) with cataract extraction and intraocular lens replacement OS in May 2016. In June 2020, she contracted COVID-19, diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction by an urgent care center. It lasted six weeks but did not require hospitalization; symptoms included debilitating bilateral pneumonia and systemic fevers and chills. In late November 2020, she presented to her local ophthalmologist with pain, redness, tenderness to palpation, photophobia, and foreign body sensation OS shortly after receiving an influenza vaccine; she denied ever having a reaction to influenza vaccines before having COVID-19. Slit lamp examination revealed 1–2+ corneal edema in the operated eye, indicating early endothelial cell rejection and promptly started on difluprednate 4 times a day for the left eye and systemic methylprednisolone pack. Signs and symptoms of rejection abated in December 2020, and steroids were slowly tapered. In February 2021, she felt acute pain OS and was found to have recurrence of signs of acute endothelial graft rejection. Resumption of topical difluprednate reversed the rejection, but pain remained. Antiviral prophylactic acyclovir 400 mg daily was started one month prior to presentation. Difluprednate was replaced with loteprednol and slowly tapered off by August 2021. She received the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccination (Johnson and Johnson Services, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Raritan, NJ), which did not aggravate the graft. She then presented to us.

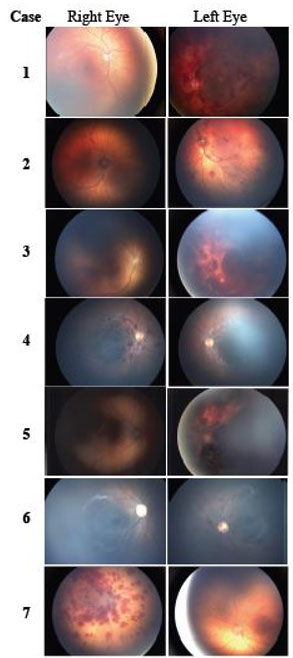

At presentation, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes, and pressures of the right and left eyes were within normal limits. Slit lamp and fundus examinations of both eyes were unremarkable. Given her history and presenting symptoms, we suspected subclinical uveitis or posterior scleritis and performed diagnostic testing. Pachymetry showed corneal thinning in the right eye and corneal thickening of the left eye (OD 472 µm, OS 589 µm). Fluorescein angiogram (FA) showed trace disc edema in both eyes (Figure 1). B-scan revealed marked sclerochoroidal thickening with suprascleral fluid accumulation in the left eye and no abnormal findings in the right eye (Figure 2). Together, these results indicated a diagnosis of posterior scleritis OS. We prescribed oral naproxen 500 mg twice daily with continuation of oral acyclovir 400 mg daily. Weekly patient reports suggested to us her eye pain remitted on this regimen, but then it recurred several months later. We had ordered serologic testing for infectious and systemic inflammatory conditions; however, the patient did not have this done through our clinic but later performed a similar serologic workup locally. Serology revealed significantly elevated ANA, suggesting a systemic root to her inflammation; however, as her rheumatologist did not find any markers of a specific disease, based on the WHO definition, her inflammation is best characterized as a systemic, inflammatory post-COVID condition. While all available evidence did not suggest a food-induced autoimmune condition such as celiac disease, the patient was able to bring her autoimmunity under control by carefully managing her diet and limiting sugary food intake since January 2022.

Discussion

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been associated with rejection of transplanted donor kidneys as well as complications for patients with heart, kidney, or lung transplants [7]. A cell-mediated response against SARS-CoV-2 infection may be implicated in this inflammatory state. Cell-mediated immunity after such an infection may be more robust than humoral immunity. It has been reported that T-cell response after SARS-CoV-1 infection may remain active 17 years after infection. Similarly, T-cell response has been shown to be stronger in severe COVID-19 patients, with CD4+ T-helper-1 cell responses more prominent than those of CD8+ T-cells. Regardless of infection severity, a T-cell response against COVID-19 can be detected more than eight months after infection [8].

Nonspecific inflammatory multisystem syndromes have been reported in patients with COVID-19 [9]. Profound immune system dysregulation during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection may incite longer-term immune alterations, immune system dysfunction, and subsequent inflammatory syndromes, though this is uncertain. Moreover, enhanced levels of IL-17 CD4+ T cells and IL-17 protein have been observed in the convalescent phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection [10]. COVID-19 has been shown to induce immunologic cross-reactivity and delayed immune responses such as a Kawasaki-like disease, immune-related vasculitis, and bilateral anterior uveitis [11],[12].

Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) is a popular procedure for corneal endothelial dysfunction with more rapid visual recovery and more predictable refractive outcome compared to traditional penetrating keratoplasty. Graft rejection in endothelial keratoplasty (EK) is rare, with a cumulative risk of graft rejection during the first 10 years is 4%, according to one study [13]. Our patient’s first symptoms started five months after SARS-CoV-2 infection and shortly after influenza vaccine. Her first episode of endothelial graft rejection occurred more than four years after DSEK surgery, and we diagnosed posterior scleritis in both eyes several months later. These symptoms arose weeks after an influenza vaccine, suggesting causation. Few cases in the literature discuss influenza vaccination and subsequent corneal graft involvement. One case report described how two individuals over the age of 65 developed signs of corneal graft rejection 2–4 weeks after influenza vaccination; for one of the patients, inflammation and graft rejection occurred after each of 2 consecutive annual vaccinations [6]. Another case report by Dr. Solomon and Dr. Frucht-Perry explained that an 80-year-old woman with history of rheumatoid arthritis and bilateral corneal grafts for Fuch’s endothelial dystrophy (FED) developed subepithelial inflammation in both grafts six weeks after influenza vaccination. Notably, the authors conclude that the autoinflammatory state of their patient made her more susceptible to flaring after vaccination [14]. In our patient’s case, her elevated ANA indicates systemic inflammation that was either exacerbated or directly caused by severe COVID-19 and then further disturbed by influenza vaccination, similar to the cases above. As she had not had such a reaction to influenza vaccinations before contracting COVID-19, her novel reaction to influenza vaccine likely arose as a sequela of COVID-19.

Given long-lasting dysregulation of cell-mediated immunity after SARS-CoV-2 infection and history of flu vaccine injection with no complications in our case herein prior to contracting COVID-19, we hypothesize that COVID-19 underlies the multisystem inflammation (corneal graft rejection and posterior scleritis OS) in our patient. Such syndromes have been described in COVID-19 patients [9]. Similar to our case, a late-onset DMEK graft rejection three weeks after presumed COVID-19 in an asymptomatic patient also supports the hypothesis of long-lasting cell-mediated immunity dysregulation and subsequent autoimmune inflammatory syndromes [15].

Conclusion

In summary, we propose that COVID-19 may promote persistent immune system dysregulation that may render ocular tissue susceptible to inflammation. Further stimulation of the immune system within months of acute COVID-19, such as with influenza vaccination, may induce graft rejection and posterior scleritis.

REFERENCES

2.

Sacchi MC, Tamiazzo S, Stobbione P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection as a trigger of autoimmune response. Clin Transl Sci 2021;14(3):898–907. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Vella LA, Rowley AH. Current insights into the pathophysiology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Curr Pediatr Rep 2021;9(4):83–92. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV; WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 2022;22(4):e102–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Jin SX, Juthani VV. Acute corneal endothelial graft rejection with coinciding COVID-19 infection. Cornea 2021;40(1):123–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Wertheim MS, Keel M, Cook SD, Tole DM. Corneal transplant rejection following influenza vaccination. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90(7):925. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Fernández-Ruiz M, Andrés A, Loinaz C, et al. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: A single-center case series from Spain. Am J Transplant 2020;20(7):1849–58. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Kaaijk P, Pimentel VO, Emmelot ME, et al. Children and adults with mild COVID-19: Dynamics of the memory T cell response up to 10 months. Front Immunol 2022;13:817876. [CrossRef]

9.

Levin M. Childhood multisystem inflammatory syndrome – A new challenge in the pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020;383(4):393–5. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Shuwa HA, Shaw TN, Knight SB, et al. Alterations in T and B cell function persist in convalescent COVID-19 patients. Med 2021;2(6):720–735.e4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: An observational cohort study. Lancet 2020;395(10239):1771–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Bettach E, Zadok D, Weill Y, Brosh K, Hanhart J. Bilateral anterior uveitis as a part of a multisystem inflammatory syndrome secondary to COVID-19 infection. J Med Virol 2021;93(1):139–40. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Vasiliauskait? I, Oellerich S, Ham L, et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: Ten-year graft survival and clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;217:114–20. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Solomon A, Frucht-Pery J. Bilateral simultaneous corneal graft rejection after influenza vaccination. Am J Ophthalmol 1996;121(6):708–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Bitton K, Dubois M, Courtin R, Panthier C, Gatinel D. Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) rejection following COVID-19 infection: A case report. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2021;23:101138. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient described herein for graciously allowing us to discuss her case. We also thank the MERSI technicians for their expertise in performing the imaging studies for this patient.

Author ContributionsAndrew H Dolinko - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Arash Maleki - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Charles Stephen Foster - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2023 Andrew H Dolinko et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.